|

deutsch |

english |

česky |

Since the moment Barbie first entered our world on 9 March 1959 at the New York Toy Fair, humankind has been divided into followers and adversaries of the blond doll. Despite her normality and gentleness, despite her artlessness and unpretentiousness, despite her peaceful nature and friendliness - the 29-centimeter-high vinyl doll again and again provokes disputes.

To feminists and critical educators the fashion doll stands for a superficial woman, who leads a dependent life, is governed by consumption and obsessed with her slim figure. Sales people and sympathetic educators are, on the other hand, convinced that the doll helps young girls try out new modalities of behaviour, pass smoothly into adulthood and learn more about the world through play. This extremely famous doll is both model and discouragement.

The picture-figure from the magazine "Bild-Zeitung", which the American businesswoman Ruth Handler used as a model for the doll Barbie, named after her daughter Barbara, already had all the characteristics that later brought Barbie fame and censure: a blond beauty with a turned-up nose,not always intellectual, but always keeping pace with the latest fashions.

As the picture Lilli Barbie, too, displays unmistakably her long-legged charm and ideal proportions. Coming after the American pin-up girls, they both appeared at a time, when after the long war years prosperity returned and people were once more discovering beauty. They felt free and loved the easy life, its attraction provided more and more by feminine charms. After the grey post-war sacrifices people loved colours. Jung women wanted to be stewardesses on the new international air-lines to satisfy their longing for world-wide travel and elegance. Barbie came at the right moment. She does not ask what is good or what is true, she just asks the feminine, all-too-feminine question: Am I beautiful?

Her many hair-dos, make-up pots, handbags, sun glasses, scarves - hers to use and for parents to buy - confirm how much store she sets by beauty. But this enormous expenditure is not necessarily only for beauty's sake. Barbie was always only as beautiful as were beautiful Esther Williams's legs, Lollobrigida's bust and Brigitte Bardot's mouth moulded in plastic.

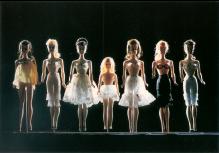

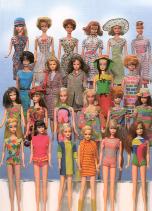

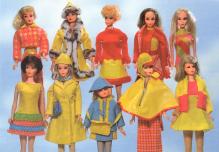

To remain beautiful, Barbie kept pace with new fashions. In the sixities the models were Audrey Hepburn and Jane Fonda, then came Cher and Farah Fawcett. Barbie got her dresses from Givenchy and Dior, subsequently she flirted with the Flower-Power enthusiasts and the disco fashion.

She joined every trend without hesitation and felt that art and society agreed with her: after all, since the sixties people viewed the world differently. There was colour TV, Pop Art and Op Art turned everyday life into art, society discarded established values. All this helped Barbie; after all, there would have been no fame for her, had people not learned to appreciate generous beauty and the colourful plastic world. Barbie revealed an almost unbelievable ability to adjust: she even became involved with the punks and thus also represented an anti-beauty movement.

Actually, to Barbie and her creators business was from the very beginning far more important than beauty. There were already 21 pieces of clothing in the wardrobe of "Barbie No.1": the doll with dark eye-shadows, sun glasses and striped bathing suit, by now forty years old and to collectors worth 10.000 US dollars, which originally sold for three dollars. Does a woman need 21 pieces of clothing to be beautiful? Presumably not.

Barbie's adversaries missed one point - the doll belongs to the tradition of dress-up dolls, since the late seventeenth century made to wear shifts and hats, fur coats and bonnets, petticoats and winter apparel. The playing of roles, used in the upbringing of the daughters from middle-class families, became with Barbie an independent enterprise: the doll is so fond of her many dresses and roles that she could quite easily produce in girls a crisis of identity.

Barbie made it always easy for her opponents to equate her beauty mania with next to no intellectual reputation. She was free and easy with such sentences as "I hate maths", until the moment the American Society of Mathematicians protested. Now she comes up with more harmless sentences, such as "I like ice-cream" or "I am fond of Ken", but these are unlikely to boost her intellectual standing.

Barbie's supporters maintain that she did not degenerate into a dependent silly. After all, she went through many professions: nurse, ballet dancer, fashion designer, down-hill skier, pilot, member of the fire brigade, baseball player. She even was an astronaut, well before Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon. She has never been a philosopher. Does a young woman really have to be a philosopher? Children would say: no. Their longing for the mostly blond doll has been satisfied more than a billion times the world over. This means that the normative power of consumption has neutralized billion times the concerns of educators.